Fatalities of disabled people in fires: Inevitable or avoidable?

Fatalities of disabled people in fires: Inevitable or avoidable?

There are 14.1 million disabled people living in the UK with tens of thousands additional people who have temporary impairments, which prevent them from evacuating their flats in an emergency- Triple A solutions.

The Grenfell Tower Fire: learning the lessons

On 14th June 2017, two hundred and twenty-three people were able to escape the Grenfell Tower fire while 72 people lost their lives.

Less well-known is the fact that almost half of the fatalities were disabled people and that there were additional fatalities due to non-disabled family members and friends staying put with disabled people when they could have safely evacuated.

Evidence submitted to the Grenfell Inquiry prompted Fazilet Hadi, Disability Rights UK Head of Policy, to state:

“…….41% of disabled people who lived in the Tower died that night. A quarter of all the children who lived in the Tower died that night. Disabled people knew they were sitting ducks should there be a disaster. They raised safety concerns which were dismissed time and again. The Inquiry has heard from residents who said they were “bullied” and “stigmatised” when they raised such concerns……”

Last year, the Local Government Fire Safety in Purpose-built Flats Guidance redacted the statement that evacuation planning for disabled people was unrealistic and unreasonable following the threat of a judicial review. The result is that all guidance follows the Home Office Guidance – Means of Escape for Disabled People. Section 1.1: Legal Overview, statement:

“Under current fire safety legislation, it is the responsibility of the person(s) having responsibility for the building to provide a fire safety risk assessment that includes an emergency evacuation plan for all people likely to be in the premises, including disabled people, and how that plan will be implemented.

Such an evacuation plan should not rely upon the intervention of the Fire and Rescue Service to make it work……”

And BS9991:2015 Section 54 states:

“Providing an accessible means of escape should be an integral part of fire safety management in all residential buildings. Fire safety management should take into account the full range of people who might use the premises, paying particular attention to the needs of disabled people.

NOTE 1 It is the responsibility of the premises management to assess the needs of all people to make a safe evacuation when formulating evacuation plans. An evacuation plan should not rely on the assistance of the fire and rescue service.”

Mythbusting: Common Perceptions & Prejudices

“All disabled people are wheelchair users”: Estimates suggest that only 10% of disabled people are wheelchair users, meaning that 90% of disabled people are not wheelchair users. As we can see from the statistics above, those with a disability are more likely to have arthritis or a hearing impairment. It is estimated that 80% of disabilities are ‘hidden’. Hidden disabilities include a learning disability, neurodiversity, mental health conditions, anxiety and epilepsy:

Mental health | The largest group | |

Arthritis | 10 million | |

Deaf or Hard of Hearing | 11 million | |

Reading difficulties | 6.3 million | |

Visual impairments | 2.5 – 3 million | |

Wheelchairs users | 1.2 million | |

(of which one third are ambulatory users) |

| |

Neurodiversity | 700,000 | |

“Disabled people prefer to stay put”: Disabled people are routinely advised that this is their safest option. Many disabled people accept this, particularly if they are told this by authority figures, such as Fire and Rescue Services. However, this is rarely an informed decision and may be based on false assumptions. Research has shown that, on average, it will be half an hour after a 999 call before a firefighter will be able to assist them in a multi-storey building. This is irrespective of whether the fire is in their flat or on their floor. Anyone remaining in the vicinity of a fire for over 20 mins has a drastically reduced chance of survival.

“Disabled people have the propensity to start fires because of cooking and smoking, lacking the incentive to evacuate”: There appears to be no data source to support these views even though these statements have been promoted by industry experts.

“If a disabled person is in a general needs block, there is every likelihood that they will be in their flat”: This is a misnomer. As with non-disabled people, disabled people frequently visit neighbours and friends in their buildings to spend the evening together.

“A buddy has to be an employee”: there is no legal requirement for any person assisting the disabled person to escape to be an employee. The requirement is that the buddy must be competent and trained. Employers should be cognisant that if an employee is involved in evacuation that this must not breach the Health & Safety at Work Act 1974 or Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999.

The Facts – Discrimination

The Equality Act 2010 states that discrimination occurs where a disabled person is treated less favourably than others.

In terms of Means of Escape, discrimination takes place where a non-disabled person has the option to leave a place of immediate danger while a disabled person has does not have the means to do so.

Discrimination against disabled people in an emergency could simply be removed by ensuring that no-one has the option to leave a building. Fire doors could be locked and only unlocked when firefighters arrived but, unsurprisingly, this is unlikely to be acceptable for society.

The Equality & Human Rights Commission has been advising disabled people that the failure to provide an assisted escape device (AED), commonly known as an evac chair, is likely to be viewed as an auxiliary aid and a breach of the Equality Act Part 4 Service Provision if not provided when requested. The high band compensation band for each breach is currently between £25,700 and £42,900.

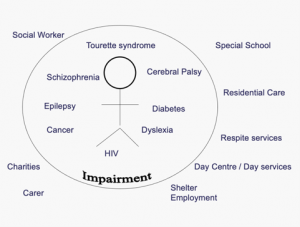

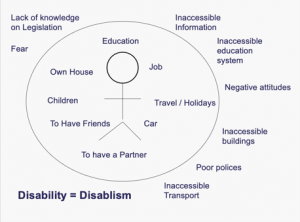

The Facts – Understanding Disability

Disabled people are all individuals with different impairments. Disability can be viewed from a number of different perspectives and can be framed in several different ways using different models of disability. These models explore the everyday experience of disabled people and how those individuals fit into community life. Depending on which model or framework we utilise, those with a disability will be perceived in different ways by others.

The Medical Model was mainly developed for the convenience of the medical professional, academics or those with an associated interest. The Medical Model focuses on the person’s impairment or condition and the services/support that society will have to provide.

The Charity Model is an offshoot of the Medical Model. The base logic is informed by the Medical Model, but expanded into a view of Disability as tragic and pitiable. According to the Charity Model, a person has a disability. This disability is a ‘problem’ in their body and good citizens should feel pity for the disabled person’s tragedy, or inspired by a disabled person’s achievements.

The Charity Model language, like Medical Model language, includes terms like normal, abnormal, the disabled, the blind, person with disabilities, able-bodied, handicapped, suffering from, special needs, needs, and wheelchair-bound.

The Social Model was developed by disabled people to provide a new way of looking at disability. The Social Model challenged the concept of the Medical Model, advocating that disability should not be considered a tragedy caused by medical conditions.

The Social Model viewpoint is that disability is linked to barriers caused by society – it is these barriers which lead to the exclusion of disabled people from society.

Resolving the Challenges

It must be remembered that many disabled people have complex conditions, which can be exacerbated or which can increase the risk of death if evacuated in an unplanned manner. As an example, a person who is a paraplegic with a spinal injury could easily become a quadriplegic if moved incorrectly by an untrained individual.

Where agreement is made with Fire and Rescue Services that they will assume the Duty of Care for a disabled person then it is essential that firefighters are trained and understand the implications of each disabled person’s impairment during an evacuation.

Mobility Impairment

Mobility impairment covers a wide range of impairments and includes not only wheelchair users but those who are non-ambulant resulting from conditions such as asthma, heart conditions such as angina and arthritis.

Disabled people with a mobility impairment will often be able to negotiate stairs slowly, but may take longer to descend than to ascend stairs.

Listed below are some of the challenges that those with mobility impairments are likely to face, the barriers likely to be present and potential solutions:

Challenge | Barriers | Solutions |

Transition | Inability to move from wheelchair or bed Availability of trained buddy assistance | Transfer board to facilitate moving from wheelchair or bed into an AED Training for buddies |

Horizontal movement | Doors: excessive door pressures and doors after a 90 degree turn Unable to walk along corridors unaided? Walking frames and sticks may block escape routes | Door pressures adjusted to ensure minimum pressure for closure Suitable Part M compliant door handles to allow door to be opened easily Additional walking aids on route to aid exit from the building Provision in escape plan for storage of walking aids to to ensure escape route is not blocked |

Vertical movement | Non-fire protected lifts which cannot be used in the event of fire Stairs: where there are no suitable handrails | Suitable handrails on both sides of stairs Carry-down techniques Clearly defined refuge areas with two-way communications Provision of suitable AEDs Installation of an evacuation lift or fire-fighting lifts |

Deaf or Hard of Hearing

Hearing impaired people may not appreciate the urgency of an emergency situation and that there is an evacuation in progress if they cannot hear commotion outside. Those disabled people with a hearing aid will remove them at night, which will increase the risk of not being alerted to a fire in their own flat by an audible sound from a domestic detector. There are also additional issues related to those with a hearing impairment which include the inability to assess where sound is coming from and a lack of urgency triggering the need to react quickly.

Challenge | Barriers | Solutions |

Hearing the alarm | Unable to hear an alarm particularly if hearing aid is removed (eg at night) | Sound enhanced alarm system Visual alarm systems with flashing beacons and vibrating pagers Vibrating pillow for use at night Vibrating alert for front door to alert if knocked |

Reacting to the alarm | Inability to assess where sound is coming from Lack of urgency to respond to an emergency An assistance dog may not pass through smoke or take an alternative route | Instructions explained using British Sign Language or Irish Sign Language Use pictograms and plain English translation Ensure disabled person is aware of alternative routes from the building |

Visual Impairment

Most visually impaired people have some level of sight. If the building characteristics are supportive, it is likely that a visually impaired people may be able to evacuate the building un-aided.

Challenge | Barriers | Solutions |

Design features | Illogical building design Lack of suitable emergency lighting Stairs with open risers | Use of colour and floor textures to define escape routes Orientation aids and tactile information Audible signals (talking signs) Avoid the use of open risers on escape routes |

Horizontal and vertical movement | Lack of contrast between walls, doors and floor surfaces Escape routes blocked | Good colour contrast on walls and floor surfaces Good colour contrast on walls and handrails Clearly defined escape routes LED lighting marking escape routes at floor level Ensure escape routes are clear of all obstructions Consider use of a tactile trail |

Way-finding information | A lack of contrasting colours and signage on horizontal and vertical routes No information of alternative escape routes | Fire safety signage following clear Print Guidelines Provision of evacuation plans in a suitable format (large print, Braille) Consider use of tactile maps and escape plans Handrails with tactile bumps |

Cognitive impairment

Disabled people with cognitive impairment includes those with learning difficulties, mental health issues, epilepsy, dyslexia, dyspraxia and autism. Those with cognitive impairment may often have difficulty in understanding what is happening during an emergency and may not have the same perception of danger as a non-disabled person.

Challenge | Barriers | Solutions |

Design features | Illogical building design Consistency of features such as colour Emergency alarms could cause overload Flashing lights could trigger epilepsy Fight, flight or freeze responses for those with autism Decibel levels of domestic detectors | Use of colour and floor textures to define escape routes Ensuring flashing lights associated with fire alarms will not trigger epilepsy Vibrating pillows or pagers Reduction in noise levels, calming by a person known to the disabled person |

Way-finding information | No information of alternative escape routes Some cognitive impairment may cause vulnerable individuals to become confused or wander | Fire safety signage following clear Print Guidelines Use of photographs, illustrations, Makaton Test drills and constant practise Buddies |

Horizontal and vertical movement | Lack of contrast between walls, doors and floor surfaces A buddy may need to comfort a distressed person before evacuation | Good colour contrast on walls and floor surfaces Clearly defined escape routes LED lighting marking escape routes Trained buddy familiar with the individual Always build in additional time in evacuation planning to comfort a distressed or confused person |

Conclusion

Some housing organisations are continuing to deny disabled residents living in general needs accommodation a Personal Emergency Evacuation Plan (PEEP) in the belief that it is unreasonable and unrealistic. This is an unsustainable position after the clear recommendations of the Grenfell Tower Phase 1 Inquiry particularly when many housing organisations and Councils have been or are in the process of implementing effective PEEPs for their disabled residents across their general needs property portfolios.

Making the most appropriate arrangements for disabled residents to evacuate a building is a clear legal duty that cannot be ignored. What is important is that disabled residents have a PEEP that identifies what the resident needs in the event of a fire or emergency to enable them to evacuate away from immediate danger safely.